We would like to start off with the recent book that you have published. Since the subject matter of the publication is Abd Al-Raman Munif's stolen library, we would like to hear more about him. How was your first encounter with him and what was striking?

In March 2015, a small part of the private library of the author and novelist Abd Al-Rahman Munif (1933-2004) was burglarized in his residence in Damascus. The theft has been addressed in many Arabic media platforms with references to the lost books and manuscripts. The estimation of the loss was taking different numbers from an interview to another one. The theft took place in the flat of the author when his wife, Suad Kawadri, was abroad. During this time, a friend's family that was displaced by the conflict in Syria was invited to stay in the flat. Months after the theft, the case was made public through a statement published by Suad Kawadri, followed by a number of press interviews. The robbery holds certain symbolism. Therefore, we decided to document all the publication of the library. The first step for Fehras was to ask the photojournalist Al-Mahdi Shubat, to document all parts of Munif's private library in agreement with his wife, Suad Kawadri. Based on detailed 407 photographs, an initial estimation of the current content of the library lists approximately 10.000 publications encompassing a wide range of fields, spanning from politics, economics, pre-Islamic and Arabic contemporary poetry to history, art and philosophy. In addition, the library includes sources such as dictionaries and lexicons, scientific and archaeological magazines as well as studies in the field of military and literature, in addition to publications in various foreign languages.

Abd Al-Rahman Munif was born in Jordan in 1933 to a Saudi Father and an Iraqi mother. Amman was the first city to shape his childhood memories, after which Munif moved to Baghdad to study law. Due to the tense political situation that followed the signing of the »Baghdad Pact« in 1952, he was forced to leave for Cairo. Munif obtained a diploma in law from Cairo University in 1975 and continued after his post-graduate studies at the University of Belgrade, where he received a PhD in Petroleum Economics, titled »Prices and Marketing«. At later stage, Munif was deprived of his Saudi citizenship due to his political standpoint, which led him to obtaining Syrian nationality. Having lived in various Arabic and European capitals in the past, he settled for a longer period of time during the eighties in Paris to work intensively on his own novels. In early 1987, Munif moved to Damascus taking his collected publications with him and integrating them into his private library there.

The idea of these books moving with Munif across the Arab cities directly speaks about the movement of knowledge in a symbolic way. Through its diversity and range of selected works, the library reflects the practice and movement of publishing in the Arab world in the second half of the last century. the library provides insights into the long history of epistemological production by publishers in the Arab world. It reflects the practice of publishing and its development during crucial political and social change. When observing this landscape within the shifting map of the Eastern Mediterranean, Munif's library points to the publishing houses that were relocated to the cities of Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo and Damascus. Some of these publishing houses no longer exist, they were established for ideological aims and disappeared later. For instance, The Center was established in Nicosia in 1983 by publisher Fakhri Karim, a member of the Communist Party in Iraq. In the late 1970s, Karim fled the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein to Beirut, but the Lebanese Civil War and the invasion of Beirut by the Israeli army in 1982 forbade him from practicing publishing. Like other Arab publishers who settled in Beirut at that time, he was forced to relocate to Cyprus, where Arab publishing practices began to unfold. The CSRS engaged with Marxist theories and published numerous books on philosophy, politics, and economy that opposed imperialism. With the demise of the Soviet Union, the Center was transformed to a space gathering Arab Marxist writers. In 1994, the head office moved to Damascus, where Karim founded Dar Al-Mada (Magnitude Books). He benefited from the opposition of the Syrian Baathist regime to the Iraqi one. Dar Al-Mada became one of the biggest private publishing houses in Syria owned by an Iraqi Immigrant. It focused on publishing works by Iraqi writers in the diaspora and also by Arab writers more broadly. The CSRS gradually came to a close in the 1990s, and Dar Al-Mada disappeared to re-appear later in Baghdad as a major publishing and media institution after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

What kind of a method did you follow while introducing the content material of the publication (When the Library Was Stolen)?

In the first attempts to interpret these photographs and to enter the sensory world of the library, Fehras presented an exhibition of the photographs in Berlin in 2015 titled, "When the Library Was Stolen." The images were the departure point for a systematic indexing process of the library archive. We extracted and captured all the information on the book spines and researched the missing information. Then, we organized the details into a list: title, author, publisher, publication year, place, dimensions, number of pages, type of publication, title of the series, number, section, month, year, volume, subject, original language, translation language, bibliographical information of the publication, digital copy, year of establishment of the publishing house, and the source for information about the publisher.

In the process of documentation and classifying the publication lists, many hidden aspects of the library's contents began to emerge. We realized that our project couldn't stop only at documenting and preserving the legacy of Munif's library – which any concerned institution could do – but that we could embark on a research of his library, an archive of modern and contemporary publications, and explore many topics pertaining to print publications. We pursued our own research interests and re-read this archive, focusing on three over- lapping themes. Given our inquiry into the migrations of the private library and of the intellectual, we first researched the terrain of Arab private libraries and their function as a repository of historical contradiction and as a cultural space that encourages thinking, production, and criticism of various historical eras. Munif's library is raw material and a starting point to research the Arab library in general and its connection to the Arab intellectual; it also offers an opportunity to explore the symbolic relationships between the publications in the library.

The book proposes a re-reading of the Arab private library archive from many perspectives. This reading interweaves the process of documentation with personal and research experiences. When the Library Was Stolen is a book in three parts. The first part features selected texts addressing the three topics: library as a space, archiving publications and publication practices in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. The second part presents the photographs of Munif's private library. These are the key documentary materials that set the foundations for the content of the book and the last part includes a catalogue documenting the publications of the library. We released the book in an exhibition in Berlin last June. The exhibition presents a re-reading of Munif's library-archive through statistical interpretation and photographs, which attempt to trace its movement, holdings, and stories. This research is based on an inventory that catalogues and documents the approx. 10,000 publications in the library.

Another work that we would like to mention in this issue is Call For Applications since it is recent and immediate response to the reality of the region from an artistic and intellectual point of view. How did you choose the writers and the essays to contribute to this particular work? How was their approach? Would you like to include a passage or a collection of quotations for us to translate for the Turkish readers?

We realised this project before we established Fehras. The book was issued by us but we prefer not to talk about it within the context of this interview. We would like to remove this question.

Villa Romana 1

"Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, statestics on a table with and 2 projections, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017"

Villa Romana 2

Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, statestics on a table, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017

Villa Romana 3

Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, statestics on a table with and 2 projections, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017

Villa Romana 4

Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, statestics on a table, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017

Villa Romana 5

Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, catalogue pages, stories in frames, and a reading table, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017

Villa Romana 6

Installation view of the exhibition »Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing«, catalogue pages and stories in frames, Fehras Publishing Practices, Villa Romana, Florence, Italy, 2017

How do you publish the books? (How are they funded? Where are they published? What kind of techniques or what kind of publishing houses do you prefer? How do you distribute them? Do you think you have a sustainable production model or do you have an idea for one regarding printed publications?)

First, the publishing house understands publication not only as printed or recorded material, but also as an expanded possibility in which readings, performances, seminars, lectures, encounters and exhibitions may act as forms of publishing. Therefore, publishing can be read as a curatorial and performative practice not only in the manner in which materials are chosen but also in the way they are released. If our publication is realized in the form of an exhibition, artwork or as a printed matter, we are depending till now on resources from the cultural funds of institutions. For instance, our publication "When The Library was Stolen" was funded bz a Berliner cultural institution. The distribution is taking over bz us and the Lebanese publisher Dar Al-Tanweer that disseminating the publication in the Arab countries. It is difficult now to think of the statue of a sustainable production within the publishing filed, because there are already a lot of complications we are facing regarding financing and distributing books. Day by day the question of sustainability becoming more important and we ask ourselves: to which extend we can reach the level of independency, while we are experiencing a gradually reduction of cultural fund in many countries?

Sharjah Biennial 1

Installation view »Bilingual Camel«, library sculpture with 35 Bilingual art publication, Fehras Publishing Practices, Sharjah Biennial 13, 2017

Sharjah Biennial 2

Installation view »Bilingual Camel«, library sculpture with 35 Bilingual art publication, Fehras Publishing Practices, Sharjah Biennial 13, 2017

Mirroring Language, Extended Dictionaries is a work that is specifically about translation. We would like to hear your thoughts about translation and your motivation to put Arabic content into context (both as translation to/from Arabic and as Arabic originals).

Since we founded Fehras, Language and writing playes an essential role in our work, considering both as fundamental parts of publishing and artistic practices. While we were outlining the first idea of the publishing house and embodying it in a written text, we asked ourselves: In which language should we produce, write and publish? Who is the observer and the reader of our work? And what is the relation between the language in use and the place of production, its nature and origin? We were conscious that being abroad in Germany and our constant use offering language and its knowledge was imposing us naturally to translate our ideas from German into Arabic. Therefore the question of power of language and aims of translation within the space of publication became very crucial.

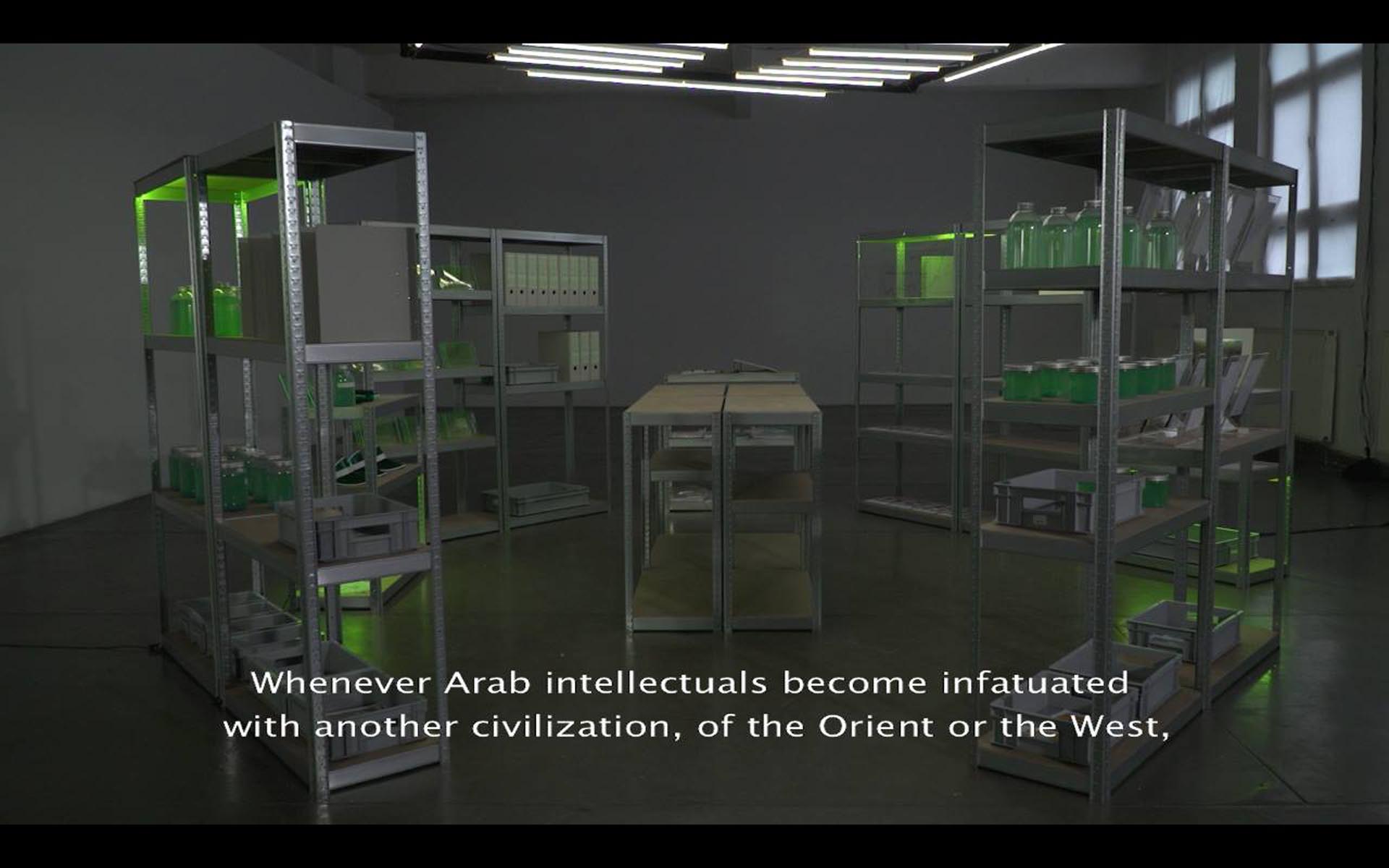

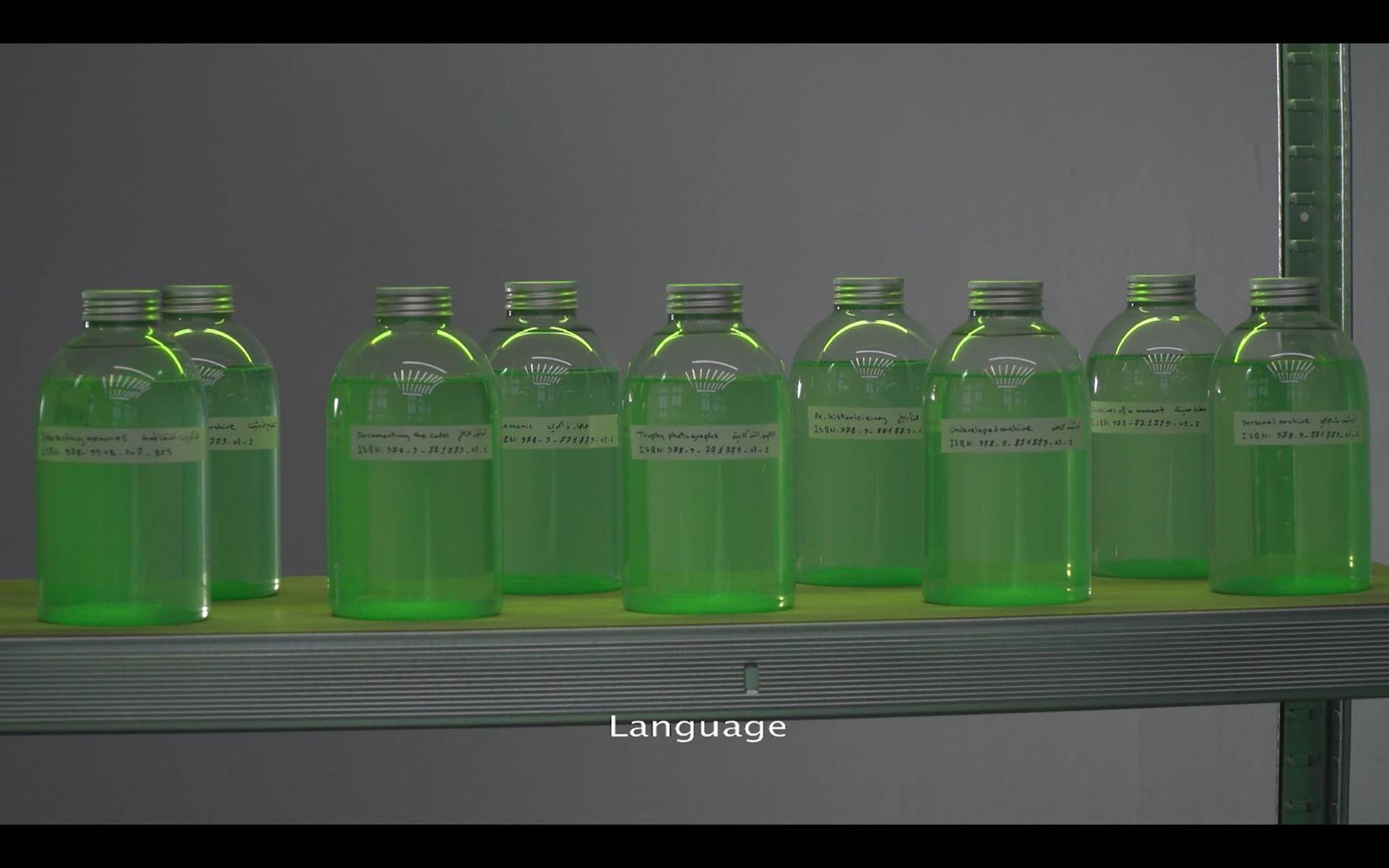

So we started with the project Mirroring Language, Extended Dictionaries that is looking at "the transformation of modern Arabic in the context of the rise of Arab cultural institutions" as a phenomenon appears in the past decades. The work concerns with the emergence of a language specific to bilingual art publications issued in the last decade in the EMNA (East Mediterranean and North Africa) region from Arab Art institutions. The research is aiming to analyse these changes on the level of form, terminology and syntax and it is structured around bilingualism, institution, translation and its methods and purposes as well as the production of cultural knowledge. It combines practices and economies of production of bilingual art publications with historical experiences on translation and cultural dictionaries making. It highlights the role of cultural institutions played in shaping the use of language aiming to understand the web of transaction governing contemporary art production in the EMNA region.

Art publications is accompanying now most of curated exhibitions, meetings, and symposia. They become crucial to institutional strategies of artists promotion and project documentation. Looking back at 1960s and 1970s, art publications were often used as a means of institutional critique whereas today, they have become institutional tools. Their role is to document projects and exhibitions, feeding and fueling the machinery of institutional production. Therefore the project is questioning, from our point of view, the role of art publication in producing language and knowledge within the power structure that covering the cultural filed.

»Soapy Postmodern Bathwater«, 24 Min., Video stills, Fehras Publishing Practices, Sharjah Biennial 13, 2017

The conceptual framework that we have chosen for this issue revolves around concepts of disenchantment/re-enchantment and etymological origin of the word disaster which is 'dés-astre' basically meaning lacking of stars. Would you like to choose a few images from your archive if anything comes to you just with the mentioning of these words?

01 Abn Rushed (Averroes) holding a book, film stills from »Al-Masser« by Yussef Shahin, 1997

02 Street-library, Al-Azbakiyya in Cairo, 2015

03 Al-Dahabi bookshop in Damascus, 2014

04 Street-library, Al-Halboun in Damascus, 2017

05 Photos of the private library of Abd Al-Rahman Munif in Damascus, 201