Freud, in an article he wrote in 1920's, says that some apparatuses, for example cameras, were by no means capable of competing with the visual storage capacity of human memory. To stress the infinitude of the visual image storage capacity, he points to the kids' favourite wipe-off magnetic boards, where before an image fades away, the new one appears, while the new image is appearing, the old one slowly disappears. What would Freud think if he would see, after about 100 years later from his ‘mystical board', that we all were besieged by a visual technology, that enables us to record, display and share every instant of our lives? If he would see that gigantic visual memory networks encompassed the images produced in a perpetual circular manner; that the velocity of this cycle was defined not by minutes or seconds but in split seconds; that the memories and the forms of visual perceptions of millions of people became ‘images' and were being immediately shared with others, so that the personal perception processes are laid bare before the eyes of the others?.. I guess, he would suggest that we could not escape death and that we were deeply immersed in narcissism!.. He might even think that the camera was now able to challenge the storage capacity of humans in a world that visualisation itself became a form of existing rather than the existence being visualised. It reminds of Vertov's cine-eye and Haraway's cyborg: Today, is it really possible to separate technology from body or soul? We live, see, think and produce through our organised apparatuses such as our telephones, cameras and personal computers.

In this day and age, photographic image, with the new meanings and functions we attribute it, is so pivotal in our lives as it has never been before: It is true that photographs have always been a memory recording tool, but today, there is this feeling that as without their recordings the memory itself would disappear (or would not even exist). Rather than taking the digital image flows in virtual environment as they are, which is only a digital photo album, we assign new meanings and purposes to them; so in these flows, identities are being built or destroyed, and the chains of images almost form our pedigrees! Without a doubt, this situation, as Nicholas Mirzoeff puts it, has an extent that glorifies the amateurship, democratises the domain of visuality, and empowers the ‘ordinary' people in the streets. The borders are also quite obscure in the realm of art: From the day that Sherrie Levine appropriated the classical photographs of the masters of photography like Weston and Evans, and by doing so challenged (and made everyone re-think about the issue) the property rights of images, there is a question that became more and more significant; who do the images belong to and what determines the right to the ownership? Here we shall consider the property rights not only in terms of the market but also of the environment the unlimited acts of seeing, recording, keeping, reproducing and sharing created. This is what the American conceptual artists of 60's used to call artistic perception and reception: If you have seen a work of art once, if it is imprinted on your mind; it, then, becomes yours.

After this lengthy prologue, I will come to the photographs of Cemre: Cemre Yeşil is a ‘unique' member of a generation of young photographers who drew attention in the last few years. I would like to separate her individual photographs from the photography projects that she wrapped around a thought. If we look from the perspective that Victor Burgin suggests, I agree that her work had two different aspects: one aspect appears to seek for a meaning and therefore is, with a more romantic notion, in pursuit of the shots on which her own particular emotions can be reflected; the other, however, is in an intellectual practice of building a meaning, which uses photographical images to deconstruct cultural phenomena. Cemre Yeşil produces remarkable works in both areas: Her individual photographs, which capture the everyday life as plain and simple as it is, sometimes ordinary and meaningless and sometimes still ordinary but meaningful, possess a very personal dimension that was woven with an unexaggerated and calm sensibility and a sophisticated sense of humour. On the other hand her photographic projects comprise a cultural interrogation of various existential forms of humanity and I believe, due to the genuine curiosity and the very finely adjusted dose of sentiment they posses, her works present a delightful visual background without excluding the intellectual depth of the project

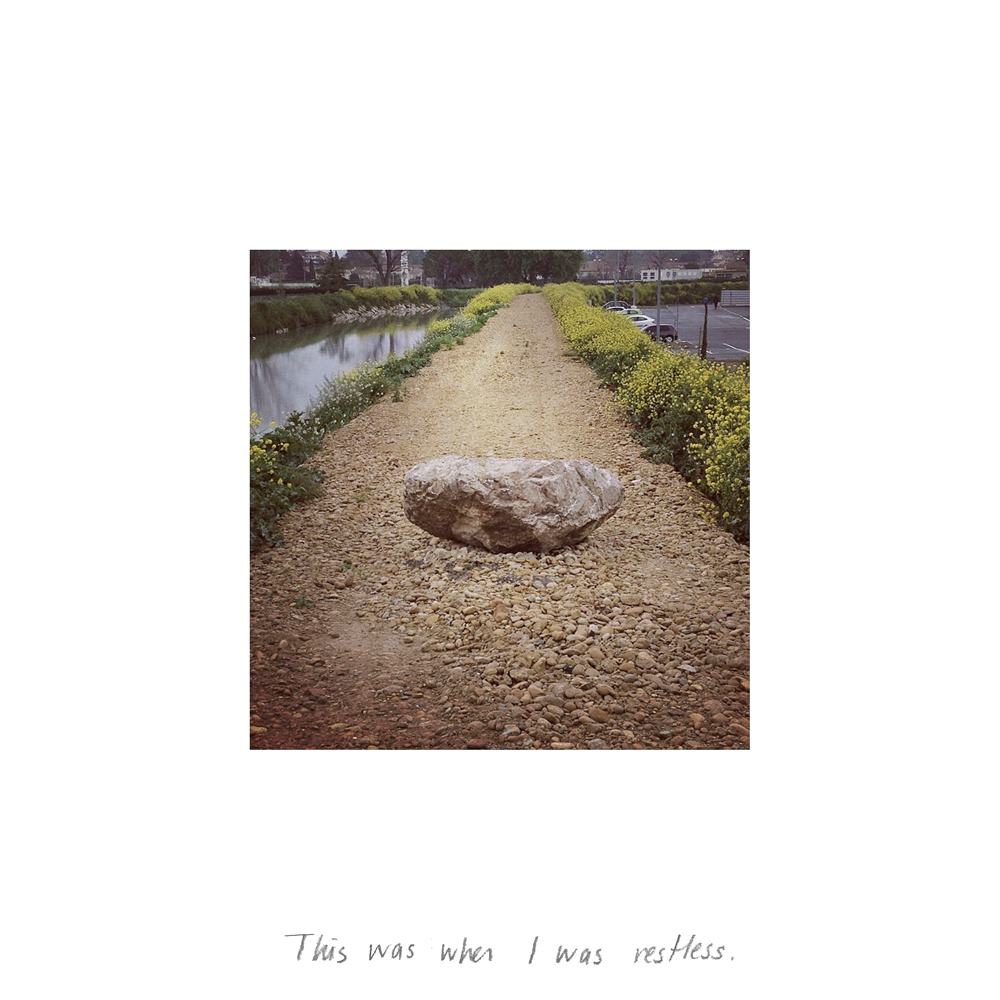

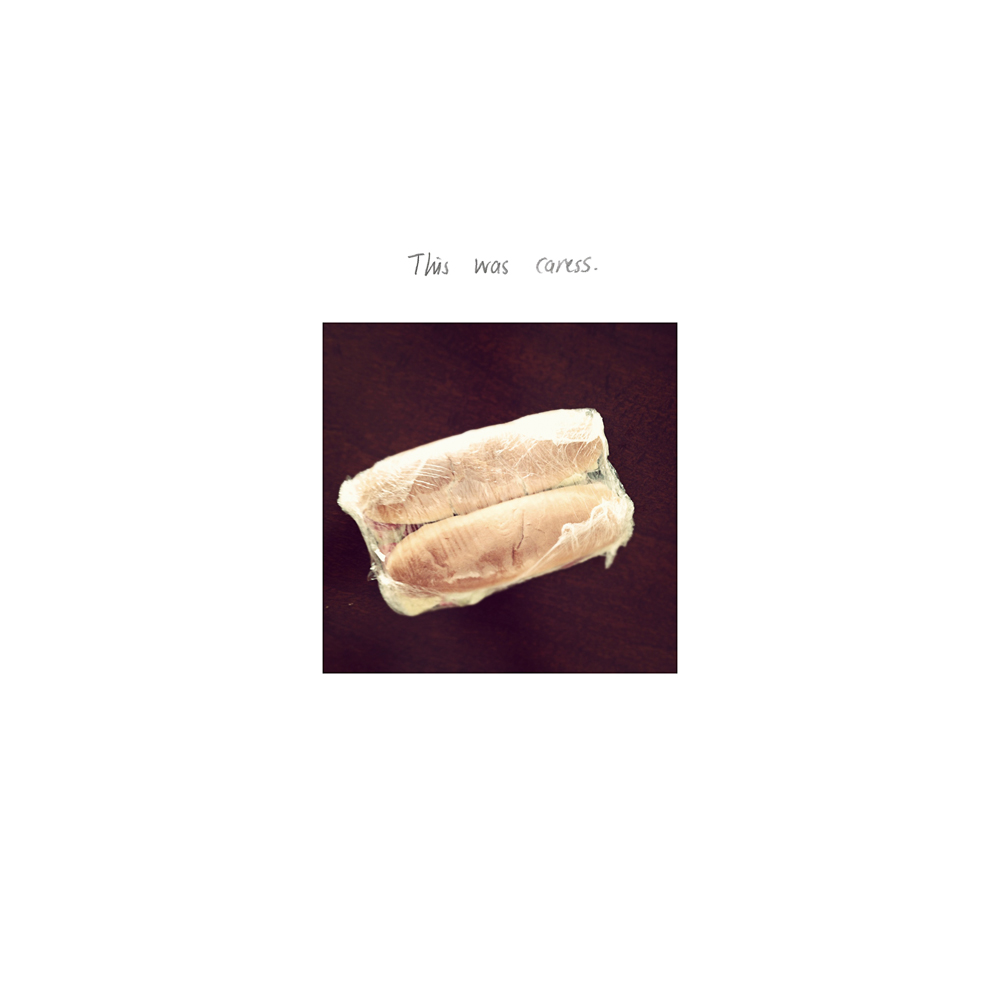

"This Was" is a project in which we can find both aspects of her work and comprehend her perspective of life and art as a photographer and an artist. The fact that all the photographs were taken with a camera phone and some of them shared on Instagram, and thus they become the reflection of a new network of visual communication produced by the virtual world, underpins the basis of the projects. That being the case, we can suggest that this project was an important interpretation of the cultural transformation I tried to describe above. Cemre refuses to be indifferent to some events from which professional photographers tend to remain aloof. In a way, she questions the meaning of being distant from the visual practices that were already diffused into our present forms of existence: Is the status of the photographic image taken with the camera phone any different than that of taken with a professional camera? Today, what does professionalism mean in terms of image production? Are the photographs a photographer shares on Instagram counted as a sort of exhibition designed through the photographer's own curatorial preferences? How do the ‘likes' one gets, or cannot get, in these virtual networks or the quantity of the followers affect the value of both the photograph and the photographer and why? What is a good photograph? What is a beautiful photograph? What does define sincerity in production of visuality? What does determine the borders between the truth and the fiction in a visual domain where everybody turns their insides out? How do the images we see and acquire so easily, become surrounded by another set of meanings, aura and legal codes, when they enter the art gallery? To what extent these questions and their answers are able to transform our artistic notions, perception of visual property and in general the visuality-based ‘system'?.. The number of the questions can be increased, but Cemre Yeşil's "This Was" project with its specific focus on personal memory, exposes the cultural conditions of sharing photographs in social media and demands us to reconsider our conception, either professional or amateur, of the status of the ‘image'.

However, this project also has a very intrinsic, very poetic characteristic, which is in fact extremely far from intellectualism, so to speak. A phrase pairing with each image, are like image/ text haikus that describe the flux of our everyday lives. The interrelation between visuality and textuality is an interesting dimension of this project, and in a world that makes us think in indicators and visual codes it drives us to reflect on the ideological structure in the background of the image production. But her attempt is completely innocent. She raises the question that how an image is able to explain a feeling or a concept by unlocking the door to her own world (or maybe pretending to unlock). To what extent are those photographs real and or to what extent are they fiction? Are those shots really corresponding to someone's life? Is it really someone's archive of memories? One can't help but wonder: Was that photograph really taken in the morning of the night that you slept in the car together?.. Really did you both fall in love with that little girl? When you were on the road, did you really see two horses like that?.. Or, each photograph's relation with memory and mystery: Why did that photograph remind you of Cemal Süreya?.. Why did you take that photograph after you lied? Was that really the happiest street you have ever seen?..

I do not know how to translate the title "This Was", which evolved while Cemre Yeşil was travelling from London to Istanbul back and forth and thus speaks writes and reads in English, into Turkish by preserving its figurative representations: Böyleydi... Buydu... İdi...? Perhaps we should just say ‘geçmiş zaman/past'. Is not photography the ‘past' itself after all?

Photography, in a way, especially due to its current function (60 millions photographs are being shared on Instagram on daily basis and until today 20 billion photographs were shared

in total) is a ritual of nostalgia in which we all have participated. As Svetlana Boym says, who argues that nostalgia was a revolt against the idea of modern times and progress, nostalgics – or perhaps all of us by engaging in a relationship with photography, so intense and indispensible than it has ever been before – are obliterating history and turning it into a personal and private or a collective mythology, we refuse to give into the past. So, if our memories, instants, were not archived, we are not considered to have lived.

This article was firstly published in the catalogue of Cemre Yeşil's exhibition, "This Was". We are publishing it with the permission of Ahu Antmen.

It is translated by Ipek Şen.